Botanical Creation & Art

Agnès Arber: Drawing to understand plant forms

At the crossroads of science and drawing, Agnès Arber, an important figure in 20th-century botany, made the observation of plants a true method of thinking.

She dedicated her life to understanding the forms of life, combining scientific precision with a sensitive eye.

Discovering Agnes Arber

Born in London in 1879, Agnes Arber grew up in a world where art played a central role: her father was a painter, her mother a sculptor. Drawing and observing forms were part of her education.

She studied at North London Collegiate School for Girls, one of the first English institutions to offer young women a solid scientific education. It was there that she discovered botany.

In 1897, she joined Newnham College, a women's college at the University of Cambridge, where botany held an important place. She successfully completed her studies there, but without an official degree: the awarding of degrees to women would not be permitted until 1948.

After Cambridge, she worked with Ethel Sargant, a British botanist renowned for her research on the structure and development of flowering plants, who became her mentor. Together, they published an article on grass seeds.

She then joined University College London, one of the first British institutions to open its degrees to women. In 1905, she obtained a doctorate in science there.

Botanical notebooks

During her years at Cambridge and later at University College London, Agnes Arber recorded her observations in a series of notebooks that mixed drawings and handwritten notes.

She draws sketches of leaves, anatomical sections, comparisons of shapes, accompanied by precise annotations on the structure of plants.

These notebooks bear witness to an attentive eye: she observes the plant by its form, before even seeking to explain it.

The drawing accompanies the research.

Agnes Arber's notebooks are now kept at the Hunt Institute.

A philosophy of plants

Her research on plant structure led her to publish several major works.

She was initially interested in the history of the first printed herbals and in 1912 she published Herbals: Their Origin and Evolution, a reference book in the history of science.

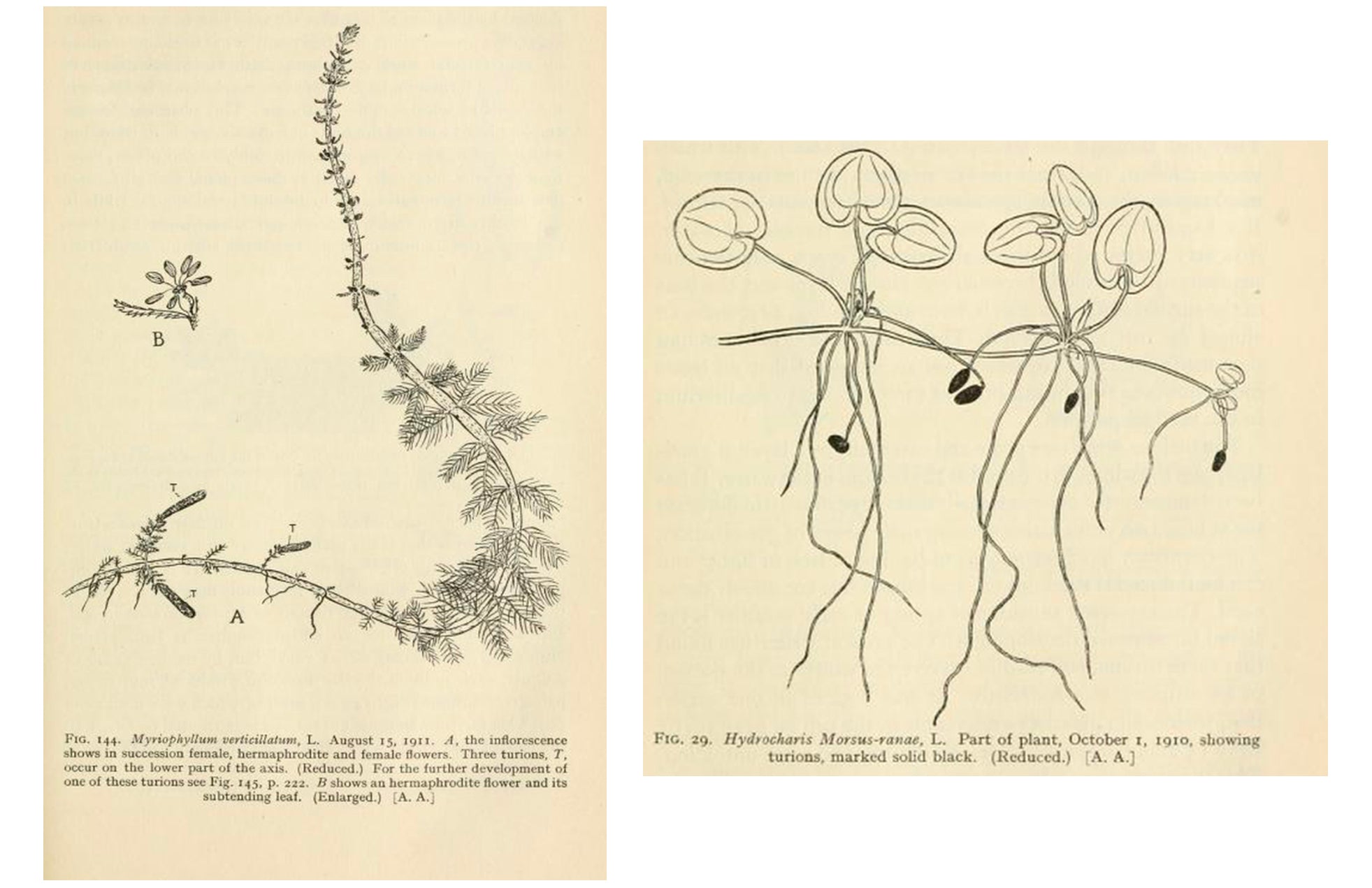

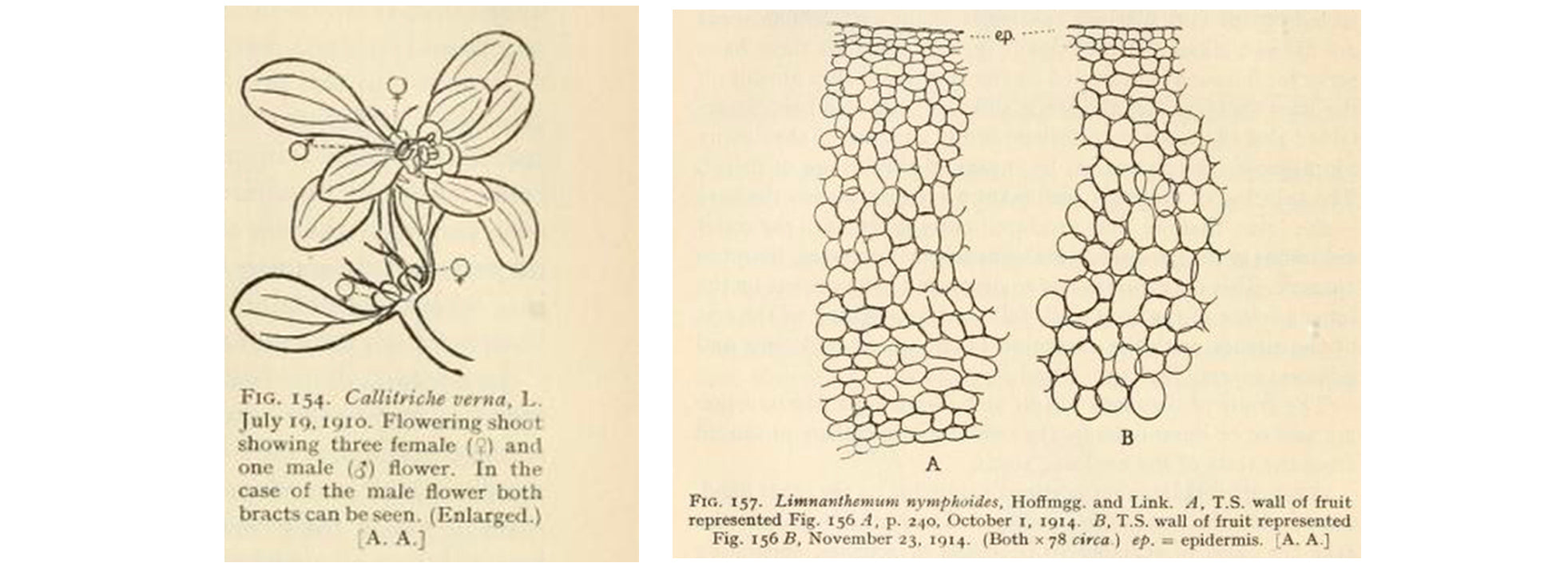

In 1920, she devoted a volume to aquatic plants, Water Plants: A Study of Aquatic Angiosperms.

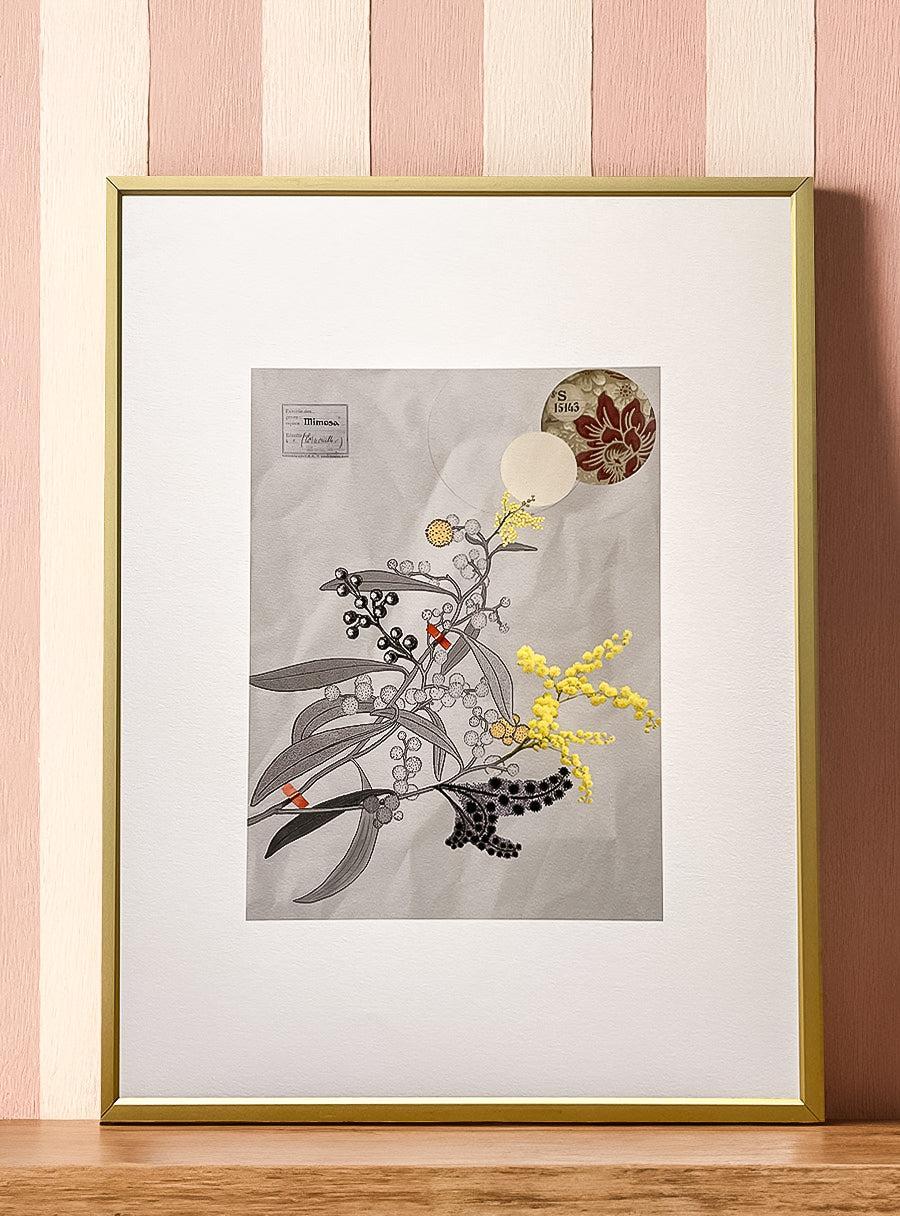

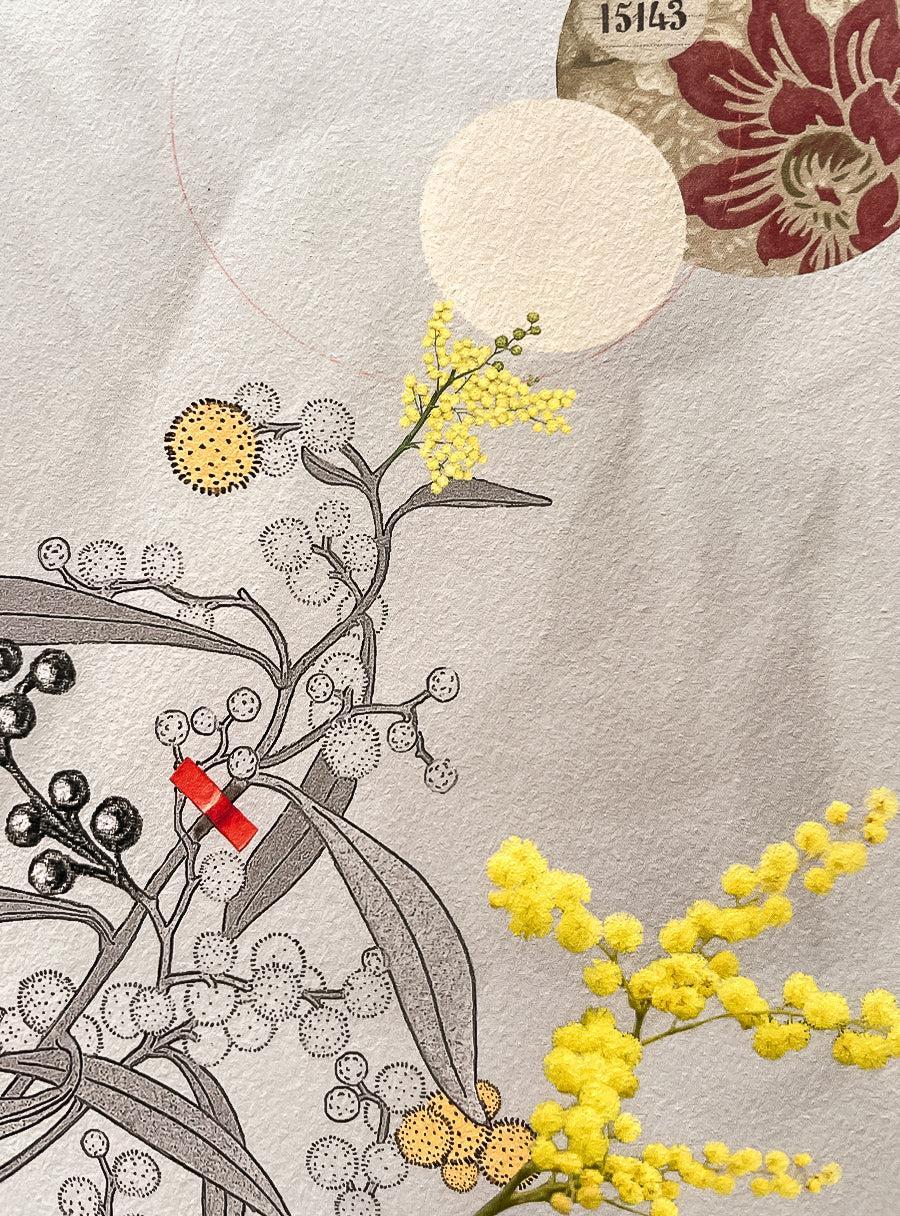

Drawings by Agnès Arber from Water Plants: A Study of Aquatic Angiosperms, 1920

Her research on plant structure led her to publish several major works.

She was initially interested in the history of the first printed herbals and in 1912 she published Herbals: Their Origin and Evolution, a reference book in the history of science.

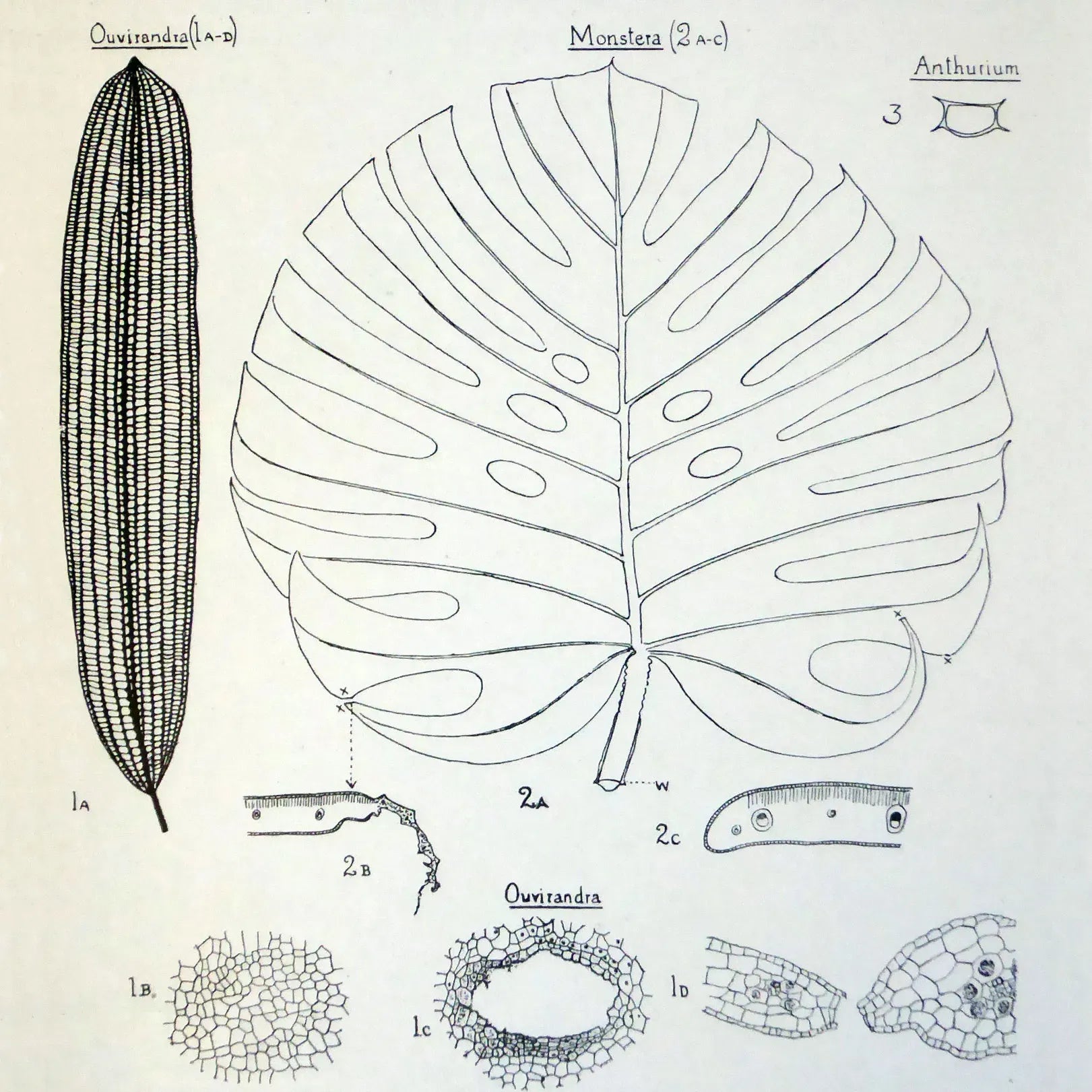

In 1920, she devoted a volume to aquatic plants, Water Plants: A Study of Aquatic Angiosperms, then deepened her work on plant morphology with Monocotyledons: A Morphological Study (1925) and Grasses: A Study of Monocotyledons (1934).

Her perspective then evolved towards a more reflective approach: in The Natural Philosophy of Plant Form (1950), she linked botany to philosophy, considering the plant no longer just as an organism to be described, but as a living form to be understood in its entirety.

Drawings by Agnes Arber taken from her book Monocotyledons: A Morphological Study , 1925

In 1946, she became the first female botanist elected to the Royal Society, a rare recognition at a time when science remained largely male-dominated.

Her perspective then evolved towards a more reflective approach: in The Natural Philosophy of Plant Form (1950), she linked botany to philosophy, considering the plant no longer just as an organism to be described, but as a living form to be understood in its entirety.

In the rigor of her lines as in the precision of her gaze, Agnès Arber creates a dialogue between science and contemplation. Her entire body of work testifies to the same attentiveness to life, between scientific rigor and a sensitive eye.